- Pacification

- Posts

- Idea for a Future History with a Buddhist Purpose

Idea for a Future History with a Buddhist Purpose

Toward technological ahimsa

The realized one has compassion for future generations. —Bodhirājakumārasutta, MN 85

The word religion comes from the Latin religare, which means “to bind.” Binding could mean compulsion, but it doesn’t have to. Often religion just patiently calls our attention to those general factors that already bind us in all situations. At its best, religion describes deep truths about the human condition and urges us not to hide or forget them.

In the last few years I’ve become religious. It’s not a development I’d expected either, and I haven’t said much about it publicly. Here I’m going to do that, and it’ll be a bit of a departure from my usual writing. I’ll likely get back to more conventional history and political theory next time, but for now, apologies.

I’ll warn you as well: My religion isn’t your religion. My religion isn’t your religion even if you’re a Buddhist. I’m also not trying for a full statement of my beliefs. I’m writing about one specific thread within them.

With that out of the way, let’s begin.

From Past to Future

Most people on earth follow an ancient religion, and one way that religion binds us is across very long timescales. Religions connect us to a distant past—even as the distant past is full of radically different beliefs and practices from ours. Sometimes those beliefs and practices are exactly this hard to understand:

Interpretive strategies arise to solve the problems we have in binding ourselves across the ages to ideas and texts that may make about as much sense as, well, that.

Scholars use the word hermeneutics to describe their attempts to interpret what are—let’s be honest—the very strange claims that religion so often makes. The word gets thrown around a lot by people who want to sound smart, but hermeneutics has real value. When a religious text says the equivalent of “the soul is a self-moving number,” we need an answer about what to do with it. And to have an answer, we need a principle that leads us to the answer, otherwise we’re just making stuff up.

Yes, “just throw the weird stuff out” is an answer, and it’s a better one than you may think, particularly for those times when a religious tradition’s pet nonsense turns vicious. All present-day religious movements, fundamentalists included, throw stuff away from time to time, even if they tell themselves otherwise. I’ll be considering and then throw some things away below, so I’m mentioning it up front.

Without at least some thoughtful, deliberate acts of hermeneutics, we’d probably only take seriously those parts of religion that already make sense to us—and those would likely be the parts that trouble us the least. We’d look past all the rest, and our religion might not change us very much. But changing us is exactly what religion should be doing.

Fundamentalism is one kind of hermeneutic, and its strategy is intuitive—so intuitive, in fact, that it can be hard not to fall into it: Fundamentalism says that we should always prefer the literal interpretation of the text. It usually adds that literalism will bring us nearer to the religion’s foundation, and thus nearer to right practice. The way to recover the good old days is to discard all the sophisticated and figurative readings.1

It’s less than clear, however, that this move succeeds, or that it’s well-grounded empirically: Basically every religious founder I can think of spoke almost constantly in figurative terms. So did their early followers; so did their later followers; so do religious authors today. Simile is the language of religion.

Fundamentalists may counter that innovation is the real problem. Innovation can’t have improved a religion, for the world itself is in decline, and figures of speech just hide the light under a bushel basket. So to speak. Let us sweep them away and hope for the best.

But fundamentalism soon runs into another obstacle: Whatever seems literal to me may not seem literal to you. That’s because “literal” is ultimately just a synonym for “unreflective” or, much worse, “personally undemanding.” It turns out that literalism isn’t a window on the past. It’s just a way of saying that we believe what we already believe.

For example, Christian fundamentalists typically say that they take the story of the Garden of Eden literally, and thus they deny the claims of modern science that contradict it. Examining those claims would entail reflection, and possibly a change from one’s already settled views. But very few fundamentalists seem fully consistent in their literalism: most Christian fundamentalists still swear, and most of them still observe a Sunday Sabbath. Yet Jesus said “Do not swear at all,” and he never said a word about changing the day of the Sabbath. That was done by Emperor Constantine in 321. But no matter; whatever the fundamentalist finds familiar, he also finds true, and he’ll think, and try to pass laws, accordingly.

Fundamentalism may be seductive, but its attempt to look back to the past is ahistorical—and human, all too human. We need better hermeneutics than this.

Consider: Is the world in decline right now? That claim can definitely be found in canonical Buddhism, just as it can in Christianity and many other faiths. But one distinctive feature of Buddhism is that the Buddhist cosmos is at least potentially capable of rising as well as declining. Quite unlike what most seem to believe in Christianity, a Buddhist’s world isn’t necessarily on a steady downward spiral until the end of days.

The Pali Canon speaks often of “many eons of the world contracting, many eons of the world expanding, many eons of the world contracting and expanding.”2 That formula comes up again and again in the Canon. It’s found in the standard description of the three knowledges that a Buddha acquires during Enlightenment. The historical Buddha realized these knowledges with his own insight, he declared, and the Canon adds that many of his followers realized them too. The scriptures say that there have been many Buddhas and Arhats who have known these things directly, through spiritual insight.

It happens that our universe is cosmologically expanding, but as I said, I’m not a fundamentalist, and so I’m not content with a merely literal reading. Literalism on this point seems both like a coincidence—and like an evasion of something much more important: Might the universe’s expansion have more to do with humanity’s growing capacities, our rapidly multiplying knowledge, our inquisitive reach, and our burgeoning ability to affect the people and creatures around us? I think it does. I think the idea of an expanding universe, taken in a human sense, has a whole lot more to teach us than a mere cosmological coincidence.3

I suggest we should reason thus: Sometimes, capacities grow, and ours are indeed growing. Not only that, but sometimes good people can take good actions, and good results can flow from them. Sometimes the Buddhas are heeded. Our powers and our morals are not always in decline. What if—right now—they’re growing? Always assuming the opposite tends to deny a basic spiritual fact in Buddhism: Good karma can be, and is, real. And when it happens to us, we should think very carefully about what to do next.

As I’ve become more of a Buddhist, I’ve consciously pursued a liberal and forward-looking hermeneutic, one that doesn’t shy away from figurative meanings if they tend to make my practice kinder, more inclusive, and more mindful of the future. The realized one has compassion for others and for future generations—and I should resolve to be like him.

It’s a part of my faith that the Buddha found a system of living and thinking about life that conduces to a certain type of especially durable and profound happiness. His core insights seem necessarily true to me, even at 2,500 years’ remove. I certainly don’t practice them perfectly, but I try. What I’d add—and I admit that this is the strange part—is that I don’t think anyone can practice the Buddha’s ideals perfectly at our current technological level.

I think we may be working up to it, and that’s why I’m writing.

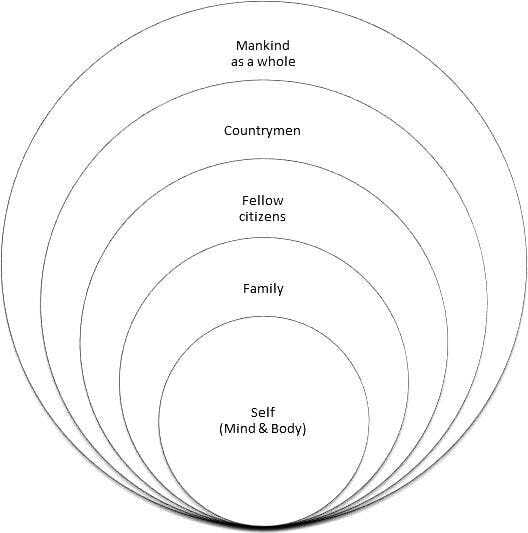

One way to think about this is with a tool from western philosophy: the circles of Hierocles. We know a lot less than we’d like about that stoic philosopher, but he invited us to imagine the moral universe as undergoing an expansion that begins with the self and progresses outward to all mankind:

Part of that progress comes from a process of reflection and moral education. Part of it also comes from having the resources and knowledge to structure one’s compassion appropriately and act on it. To aid one’s fellow citizens does not entail the same actions in all cases as aiding one’s family; if it did, the passage from one circle to the next would be trivial. There is learning to be done at every stage. Intriguingly, Hierocles also appears to have argued in favor of animal sentience. Our moral duties with regard to the animals won’t be quite the same as those with regard to our families—but might we expand the circles of our concern? And if we can, why shouldn’t we?

A civilization of the far future can probably achieve certain Buddhist ideals much more completely than they have so far been realized at any point in the religion’s history. My futurist hermeneutic places its hopes with such a civilization, and not with the distant past.

Not As Crazy As It Seems

What would Buddhism look like if we deliberately applied a futurist hermeneutic? What if we said, for example, that the Pali Canon wasn’t written for today, and wasn’t written for us to live exactly as the Buddha’s contemporaries did either, but rather, what if we said: the Pali Canon was written for its ideals to be realized in the fullness of time, with such resources as the future may possess?

The point here isn’t to try to be liberal by saving every old scrap of text with some clever new gloss, which some contemporary writers have done. Some parts of the Canon probably can’t be saved convincingly at all. But even if they can, it’s much more productive simply to ask: What would a Buddha do in our time, and with our resources? And what would a Buddha do with even greater resources than our own?

What if those resources were vastly greater?

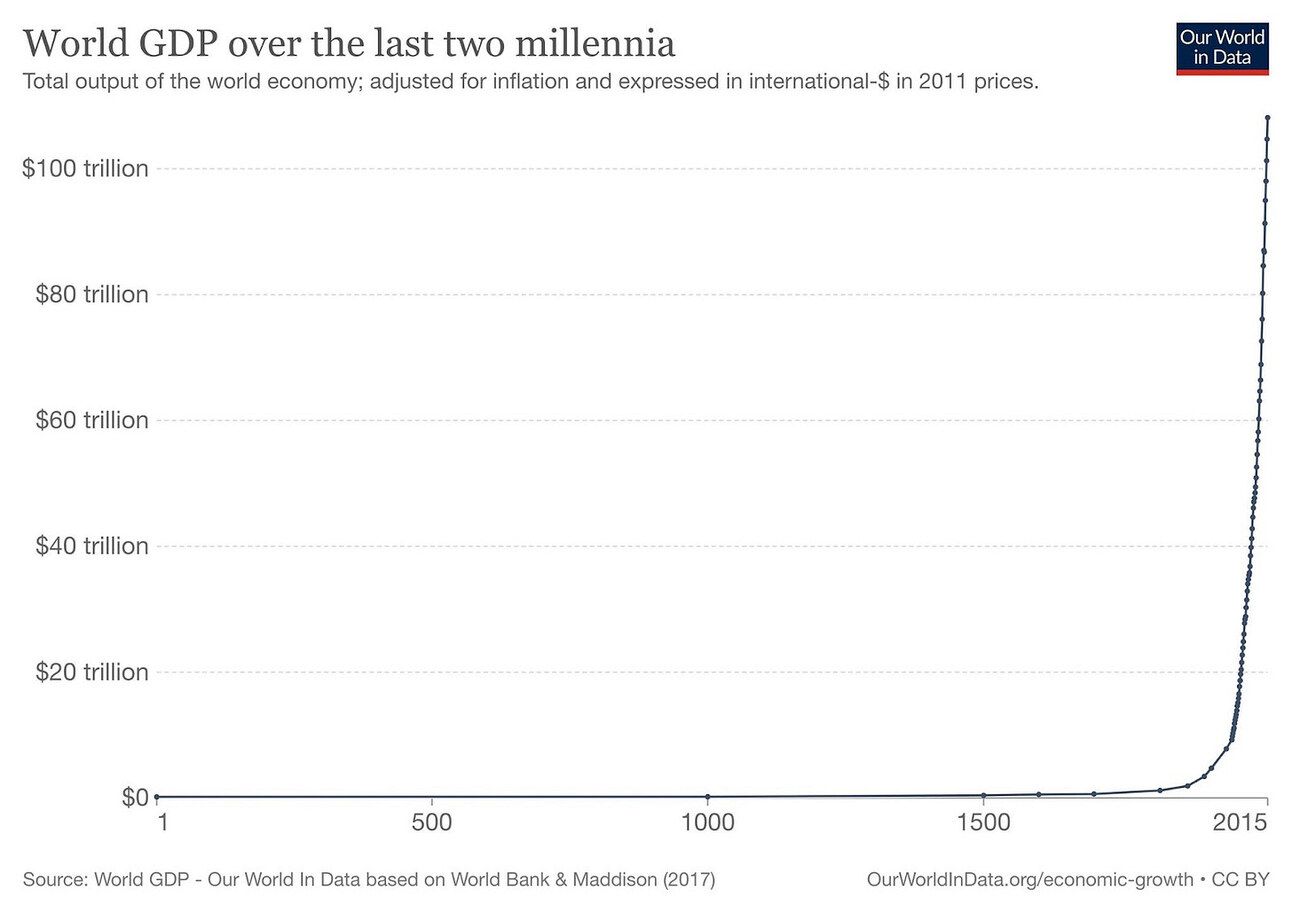

We should certainly be asking that question, because our resources are indeed expanding, and they’re growing much faster than our population. While this trend can be hard to see in the course of any one person’s life, it’s impossible for a historian of economics to deny it:

Extreme poverty is vanishing worldwide. Literacy and health are improving. Wherever on earth you live, you are almost certainly richer than your grandparents were at a similar age. Compare your wealth to that of your great-great grandparents, and you live in a world that has been utterly transformed. You have everyday capacities that they would struggle to imagine.

See any recessions on that graph? No—and that’s because, while a recession can be terrible in the life of an individual, the trend against which recessions take place has always ended up dwarfing them in just a few short years. We need to consider the reality of our species, and this is it.

Compare your life to that of a fifteenth-century peasant, and you—yes you—are kind of like a lesser god to them. And that’s true even if you’re far from rich today. The very highest echelons of the upper classes from that time would have more gold than you, probably. But be honest: You’d rather have a phone or a car or a TV than the equivalent in gold. You almost certainly do, and they never could. Having gold was the best they could do. It was mostly a status symbol, and it did basically nothing to increase past people’s capacities for learning, sharing, or caring for one another. Ancient moralists have always had a certain contempt for gold, and maybe there’s a modern answer for why that was.

Yes: Exploitation certainly exists, but most of our wealth isn’t produced by it. Indeed, exploitation at best moves wealth around—with tremendous loss and suffering in the process. What we as a species have been doing since the Industrial Revolution includes some exploitation, to be sure, but mostly it’s been honest toil. Not pleasant, but worth it in light of the rewards.

Humanity’s economic history should be thought of as century upon century of dearth—and then, suddenly, an explosion of wealth, one founded on specialization and gains from trade, both of which harness new sources of energy through new knowledge about how the world works. Will it be permanent? No; nothing ever is. That’s fundamental in Buddhism. But our contemporary wealth clearly isn’t just a bubble either. We’ve learned things that will be almost impossible to forget. The resources we now use aren’t inexhaustible, but they’re increasingly renewable. In all there’s a lot more reason to start considering how to behave in an indefinitely wealthy future— and a lot less to expect that the end is near.

Economic historian Deirdre McCloskey calls this nearly universal enrichment the Great Fact. The enrichment that commerce, technology, and industry have produced has been so different and so alien to traditional systems of thought—Buddhism included—that it’s hard to think clearly about what this Great Fact may entail ethically or spiritually. But in addressing the timeless problems, we can bring new resources to bear, and we shouldn’t be ashamed to say it. Quite possibly those resources can provide new answers already. And almost certainly, if present trends continue, the answers of the far future will be different again from our own.

To be sure, a Buddhist futurism would suffer some of the same problems as a Buddhist fundamentalism: It would often lead us back to ideas that were already our own, just dressed in a saffron robe. But these wouldn’t be—they couldn’t possibly be—the same ideas found in fundamentalism. A Buddhist futurism would have to ask different questions and lead to different places.

I look at the graph of world GDP, and I see a universe of expanding human capacities. Those capacities, however, can be used for good or for evil. The challenge to one who lives in a universe of expanding capacity is to learn to use that capacity wisely.

Cruelty and Ahimsa

Cruelty is a constant feature of human life—and it has a constant tendency to hide. We usually let it. True religion, though, generally returns cruelty to our attention, just as it does with all the important things. It does so calmly, patiently, and to our great embarrassment. Any religion that’s worth the effort will never let cruelty hide in the status quo, or in euphemism, or in clever arguments. The Buddha’s most direct answer to cruelty can be found in the Dhammapada, a canonical collection of the Buddha’s sayings in which we read:

“They abused me, they hurt me,

they defeated me, they robbed me!”

For those who hold on to this

hostility is never replaced by peace.

“They abused me, they hurt me,

they defeated me, they robbed me!”

For those who do not hold on to this

hostility is replaced by peace.

Hostility is never pacified

by means of hostility.

Only by means of non-hostility is it pacified.

In one sutra, we find the Buddha instructing his monks as follows:

Even if low-down bandits were to sever you limb from limb, anyone who had a malevolent thought on that account would not be following my instructions. If that happens, you should train like this: ‘Our minds will remain unaffected. We will blurt out no bad words. We will remain full of compassion, with a heart of love and no secret hate. We will meditate spreading a heart of love to that person. And with them as a basis, we will meditate spreading a heart full of love to everyone in the world—abundant, expansive, limitless, free of enmity and ill will.’ That’s how you should train…

“So, mendicants, you should frequently reflect on this advice, the simile of the saw. This will be for your lasting welfare and happiness.”

As bandits sever your limbs, don’t even have a malevolent thought: How much less should we practice cruelty in response to someone’s words—and how much less should we practice cruelty for the sake of sensual pleasure! And yet we do. We always have. Here are just three paragraphs from a long canonical litany against merely sensual pleasures:

[F]or the sake of sensual pleasures kings fight with kings, aristocrats fight with aristocrats, brahmins fight with brahmins, and householders fight with householders. A mother fights with her child, child with mother, father with child, and child with father. Brother fights with brother, brother with sister, sister with brother, and friend fights with friend. Once they’ve started quarreling, arguing, and disputing, they attack each other with fists, stones, rods, and swords, resulting in death and deadly pain. This too is a drawback of sensual pleasures apparent in this very life, a mass of suffering caused by sensual pleasures.

Furthermore, for the sake of sensual pleasures they don their sword and shield, fasten their bow and arrows, and plunge into a battle massed on both sides, with arrows and spears flying and swords flashing. There they are struck with arrows and spears, and their heads are chopped off, resulting in death and deadly pain. This too is a drawback of sensual pleasures apparent in this very life, a mass of suffering caused by sensual pleasures.

Furthermore, for the sake of sensual pleasures they don their sword and shield, fasten their bow and arrows, and charge wetly plastered bastions, with arrows and spears flying and swords flashing. There they are struck with arrows and spears, splashed with dung, crushed with spiked blocks, and their heads are chopped off, resulting in death and deadly pain. This too is a drawback of sensual pleasures apparent in this very life, a mass of suffering caused by sensual pleasures.

One class of sensual pleasures comes from eating meat, or rather, from our exploitation of the animal kingdom in general. We ought not to look away from this cruelty: We raise animals deliberately, under torture, for the sake of our palates. The book Dialogues on Ethical Vegetarianism by philosopher Michael Huemer walks through the case against carnivory so clearly and so convincingly that it’s hard to find any remaining excuse for these practices. I’ve been a carnivore for most of my life, but lately I’ve been taking steps toward veganism and removing animal products from my diet, even against the strong objections of my family.

We’ve been here before as a species, and not even all that long ago. Slavery has existed since ancient times. The Canon speaks of slaves; the Roman Empire had them; the supposedly civilized western world kept them until the nineteenth century. Again and again, we looked away, and moralists did their best to bring the cruelty to our attention. As a slave says in Voltaire’s Candide: “When we work in the sugar factories, and when the mill catches a finger, they cut off our hands. When we want to escape, they cut off a leg. Both of those happened to me. That’s the price for you eating sugar in Europe.” It only took another century for us to act.

And yet we shouldn’t stop there. Factory farming, and indeed all animal food, always entails cruelty. But even farming vegetable sources of food causes untold amounts of animal suffering. When fields are cleared, plowed, sown, and harvested, insects and rodents are killed. Some carnivore philosophers have delighted in pointing this out. They use it to excuse carnivory; the argument runs that all food is tainted by cruelty—and thus cruelty is implicit in all human life—and thus they might as well eat meat. Which is to say, they see that some are bad to a certain degree, and they take it as permission to be even worse. Such a clever, clever means of looking away.

The solution found in Theravada Buddhism, at least so far, has been that some cruelties are indeed unavoidable for lay people, but that the monastic order, by not participating in agriculture, and by accepting only food that is freely given, can separate itself from the cruelty of the world. The monastic life is already demanding, and it’s already beyond the usual person’s reach for many other reasons. We shouldn’t expect it to be universalizable or practiced by everyone. We lay people support the monks and nuns, and they live lives that we cannot. With good karma, there can one day be a rebirth for us in that type of life.

But will it always have to be that way? Even the monastic strategy relies, in effect, on the cruelty of others. For non-monastics, and at least for now, there is only a life of greater or lesser cruelty. The carnivore philosophers are correct that there isn’t a life without it. Obviously we should opt for less cruelty—but we should also recognize that a day may be coming when none of us need any cruelty at all. If we could use minerals, plants, bacteria, fungi, and other non-sentient life to meet all of our nutritional requirements, and if we could do so entirely removed from harms to the animal kingdom, then the choice seems clear: We should absolutely do it.

In the meantime, we should lay the groundwork for what could be a species-wide choice to live entirely apart from cruelty. It might not be the case that everyone in the species will choose it—some certainly won’t—but what if we could? And how can we get to the point where it’s a viable option? What I have in mind could be something like a self-sustaining vegan arcology, one that might indeed require some cruelty to set up, but that could be lived in, with food and energy needs entirely fulfilled, without fear of harming any creature at all.

As a few preliminaries, we should say yes to lab-grown meat—emphatically, and not just apologetically. It should be seen as a first step toward something much greater. We should say yes to other synthetic foods that are more and more free from cruelty. We should encourage progress in the life sciences that will increasingly separate us from our primitive origins in animal husbandry and conventional agriculture. We should strive for, and hopefully achieve, technological ahimsa: the attainment of the ancient spiritual end of harmlessness, by the means of advanced technology. A futurist rather than a primitivist veganism, one that aims at ending our long abusive relationship with the animal kingdom.

Perhaps that goal will prove impossible while humanity remains on earth. Our interactions with the biosphere have so far been pretty constant, and given the energies and scales of human activity in the far future, it may prove that we can’t keep all wildlife from harm’s way, not even with the best of wills and the best of technologies. Our trajectory has so far been toward greater and not lesser environmental harm. Must it stay that way? No, of course not.

In the Culture novels by Iain M. Banks, the more or less post-scarcity humanoids who populate the eponymous Culture have long ago retreated from planetary life, and for exactly this reason. They spend most of their time in interstellar spacecraft, and they are suspicious of any civilizations that haven’t managed to do likewise. Biospheres are best left to their own devices, or only explored as a matter of occasional tourism. A proper civilization can do better by not exploiting them at all. The sutras speak of those who meditate blissfully, knowing that they enjoy a blameless happiness—and isn’t this an approach to that? Shouldn’t we want to be like them? Obviously one could still do plenty of harm, and one could still harbor lots of ill-will, even while living in a vegan space habitat. Banks’s characters sure do. But if I wanted to practice ahimsa perfectly, it seems like living in a Culture habitat would be a fine start.

Other forms of technological ahimsa may eventually exist as well: An uploaded consciousness wouldn’t need any animal products, and the energy to run it wouldn’t need to come from a biosphere at all. EMs—computer-emulated human minds—could in principle be harmless to all other types of creatures. If an emulated consciousness still wanted to eat emulated meat—well, by that point in our development, emulating the experience of eating meat would be trivial. The fruits of cruelty could retreat to within the emulated mindspace, where their origins need not be cruel. We could even fight brutal virtual blood sports if we wished. (But I hope we wouldn’t. It’s not good to cultivate cruel thoughts.)

An EM could always wrongfully desire to harm non-emulated living creatures in particular, but it’s hard to see why it would want to. Ahimsa would probably be much easier for an EM than for us, and it’s good to make virtue easier to practice.4

These futuristic developments would much better satisfy the ancient ideal of ahimsa than any traditional form of agriculture. They don’t seem to depend even on mediated cruelty. But progress toward them would look, feel, and maybe even taste very artificial. We should bite the bullet and do it anyway. In the near term, we should embrace meat substitutes if necessary to counter the craving for meat. In the longer term, we should look forward to greatly advanced biotechnology, and we should cheer when developments in this direction occur. In the very longest of terms, we should look forward to becoming something that traditionalists might not even call human.

But with Humility?

This all sounds utopian, and I swear I don’t mean it to. We seem to be on a course of technological development that opens up a lot of different interesting possibilities, and something like this is simply one of them. I don’t say, directly, “Let’s get to work on this” because I don’t think I know enough to know where the next steps are exactly. Please don’t go building any arcologies tomorrow. I would stay far away from anyone who did. So should you.

I only know two things: First, that we can live in better and in less cruel ways right now than we could live in previous times. And second, that we have reason to hope for further improvement in the future, above all in the far future—which may transform humanity and its livelihood in ways that fundamentally alter our relationship to the animal kingdom, the biosphere, and perhaps to cruelty itself. We should continue the search for less cruel ways of life.

But there’s a special kind of disaster to avoid here. It lies in pursuing the project too diligently, in turning others’ lives into misery for the sake of the far-off ideal, one that the pursuer doesn’t even necessarily see clearly enough to act on in his own life. The Buddha often warned that there were four kinds of mortifications:

One person mortifies themselves, committed to the practice of mortifying themselves.

One person mortifies others, committed to the practice of mortifying others.

One person mortifies themselves and others, committed to the practice of mortifying themselves and others.

One person doesn’t mortify either themselves or others, committed to the practice of not mortifying themselves or others. They live without wishes in the present life, extinguished, cooled, experiencing bliss, having become holy in themselves.

The first person is a straightforward self-harming ascetic, committed to painful practices in the belief that they lead to eventual happiness. The Buddha’s Middle Way teaching rejects this approach to spirituality. The second person “is a slaughterer of sheep, pigs, poultry, or deer, a hunter or fisher, a bandit, an executioner, a butcher of cattle, a jailer, or has some other cruel livelihood.” Clearly we shouldn’t be that sort of person either. The third person is one we have seen way too often in modern history:

It’s when a person is an anointed aristocratic king or a well-to-do brahmin. He has a new temple built to the east of the city. He shaves off his hair and beard, dresses in a rough antelope hide, and smears his body with ghee and oil. Scratching his back with antlers, he enters the temple with his chief queen and the brahmin high priest. There he lies on the bare ground strewn with grass. The king feeds on the milk from one teat of a cow that has a calf of the same color. The chief queen feeds on the milk from the second teat. The brahmin high priest feeds on the milk from the third teat. The milk from the fourth teat is served to the sacred flame. The calf feeds on the remainder. He says: ‘Slaughter this many bulls, bullocks, heifers, goats, rams, and horses for the sacrifice! Fell this many trees and reap this much grass for the sacrificial equipment!’ His bondservants, employees, and workers do their jobs under threat of punishment and danger, weeping with tearful faces. This is called a person who mortifies themselves and others, being committed to the practice of mortifying themselves and others.

Vast civilizational projects are dangerous, and their danger looks a whole lot like this. If anything, our added resources and capacities only make it worse. Those who built the pyramids—and those who undertook the Great Leap Forward—are the third type of person in this teaching. We must avoid being like them, so we’ll need to pursue technological ahimsa both gently and humbly, mortifying neither self nor others.

Part of this is that we don’t know which directions our growing capacities will lead us. It won’t be any good to torture self and others for the sake of, say, mind uploading—when interstellar travel and biosphere escape turn out to be, in retrospect, the better ways to go. Or vice versa. Outside of some general outlines, our ability to see the future is limited by a simple fact: If we could predict the future of technological development with any certainty, then to that degree, we could instantiate it today. If you want to bet on biosphere escape, go ahead, but do it with your own resources, and by building the things that you know how to build. Others will do similarly for other projects. I don’t know which one will win, and neither does anyone else. Don’t become a slave driver for them.

Suppose someone perfects technological ahimsa. What then? Presumably many people who wished to practice harmlessness would start living in arcologies or space colonies, eating artificially cultured foods, and doing absolutely no harm to sentient beings. Truly such people might experience—much more than any before them—the blameless happiness of which the scriptures speak. More than any, they could live the Brahmaviharas: the dispositions of benevolence toward all beings that the scriptures praise, and that the inhabitants of a future harmless society could say, at least of themselves, that they practice perfectly.

You’ve likely heard of metta, the disposition of loving kindness, or loving friendliness, which is the first of these. It’s sometimes expressed in the English mantra “May all beings be happy. May all beings be at peace.” A civilization that made it possible for all willing individuals to live in perfect or near-perfect ahimsa could allow one to reflect that they had harmed no one, whether human or animal, at any time in their lives.

Humanity, though, isn’t mine to shape. I suspect that making ahimsa a practical life option for the masses will also lead to an ideological hardening around cruelty as a positive good. It won’t do to retrace Kant’s optimism in his Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Purpose:

However obscure their causes, history, which is concerned with narrating these appearances, permits us to hope that if we attend to the play of freedom of the human will in the large, we may be able to discern a regular movement in it, and that what seems complex and chaotic in the single individual may be seen from the standpoint of the human race as a whole to be a steady and progressive though slow evolution of its original endowment.

Buddhism is pretty idealist as religions go, but I don’t think it can follow Kant here. Remember, the universe can contract. Our capacities don’t tend naturally to achieve their ends. Or if they do, some other process, one that’s equally natural, can always step in at some point and upset things. The sutras are full of warnings against decline, and some of them straightforwardly predict it. Conditions are impermanent, and nothing is secure outside Nirvana.

So what this essay is about isn’t really predicting the end goal of all of mankind, or enlisting you all in a movement, or fulfilling humanity’s natural destiny. It’s about the set of possible future histories that I could will to be true, and that I could—and do—hope will have some greater purchase in time. It’s about refusing to look away from cruelty. And it’s about continuing the search for ways to lessen it.

Reply